1Department of Laboratory Medicine and Paik Institute for Clinical Research, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea

2Department of Biomedical Laboratory Science, Inje University, Gimhae, Korea.

3Department of Laboratory Medicine, Wonkwang University Medical School, Iksan, Korea

4Department of Laboratory Medicine and Research Institute of Bacterial Resistance, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

5Department of Laboratory Medicine, Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Hwaseong, Korea

6Department of Laboratory Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea

7Department of Laboratory Medicine, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

8Department of Laboratory Medicine, Jeju National University College of Medicine, Jeju, Korea

9Department of Laboratory Medicine, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

10Department of Laboratory Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea

11Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea

Correspondence to Jeong Hwan Shin, E-mail: jhsmile@paik.ac.kr

Ann Clin Microbiol 2025;28(4):23. https://doi.org/10.5145/ACM.2025.28.4.4

Received on 2 October 2025, Revised on 18 November 2025, Accepted on 27 November 2025, Published on 20 December 2025.

Copyright © Korean Society of Clinical Microbiology.

This is an Open Access article which is freely available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Background: Haemophilus influenzae is the causative pathogen for various infectious diseases, such as respiratory infections, otitis media, sinusitis, and meningitis. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and molecular characteristics of β-lactam resistance in non-typeable H. influenzae isolates in South Korea.

Methods: In total, 115 non-duplicated H. influenzae isolates were included in this study. Bacterial identification and serotyping were performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of bexA, respectively. Antimicrobial susceptibility was tested using the broth microdilution method. The production of β-lactamase was determined using nitrocefin disks. The presence of blaTEM and blaROB was confirmed using PCR. ftsI was analyzed to identify amino acid mutations in penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 3.

Results: Resistance rates to ampicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate, and cefuroxime were 67.8%, 13.9%, and 32.2%, respectively. None of the isolates were resistant to cefotaxime or ceftriaxone. Among 78 ampicillin-resistant isolates, 71 were β-lactamase-producing ampicillin-resistant (BLPAR), and 7 were β-lactamase-non-producing ampicillin-resistant. All BLPAR isolates carried blaTEM, and none carried blaROB. Among 16 amoxicillin–clavulanate-resistant isolates, 15 β-lactamase producers harbored blaTEM. Four to 7 PBP3 mutations per isolate were detected in all 16 non-β-lactamase-producing ampicillin-resistant or cephalosporin-resistant isolates.

Conclusion: β-lactam resistance in non-typeable H. influenzae isolates is highly prevalent in South Korea, primarily because of blaTEM and various PBP3 mutations. Therefore, continuous monitoring of antimicrobial resistance rates and mechanisms in non-typeable H. influenzae is necessary.

Bacterial drug resistance, Beta-lactamases, Beta-lactam resistance, Haemophilus influenzae

Haemophilus influenzae is the causative pathogen for various infectious diseases such as respiratory infections, otitis media, sinusitis, and meningitis. H. influenzae is classified into six encapsulated groups (serotypes a–f) and a non-encapsulated group (non-typeable H. influenzae; NTHi). H. influenzae serotype b (Hib) is a well-known pathogen that causes serious invasive infections [1]. Recently, the number of invasive infections caused by Hib has significantly decreased with the global introduction of the Hib vaccine, whereas the number of infections caused by NTHi has increased [2,3]. NTHi is a common cause of bronchitis, acute otitis media, and sinusitis, particularly in individuals with underlying airway damage [2,3]. Unlike encapsulated strains, NTHi show high pharyngeal colonization rates, often exceeding 70%, with a particularly high prevalence in young children [3].

Ampicillin remains the first-line therapy for NTHi infection, but resistance has steadily increased [1,2,4]. This increase is driven by both the acquisition of β-lactamase and mutations in the penicillin-binding protein (PBP). Notably, PBP mutations are constantly evolving, resulting in cross-resistance to cephalosporins and carbapenems as well as increased ampicillin resistance. PBP3 mutations are reported to occur more frequently in Japan and South Korea [5,6].

In 2024, the World Health Organization highlighted ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae as one of the 15 most critical antimicrobial-resistant bacteria that pose a global threat to human health, calling for ongoing surveillance and monitoring [7]. In addition, β-lactamase-producing amoxicillin–clavulanate-resistant (BLPACR) H. influenzae has emerged and spread in a few countries [2,4].

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and molecular characteristics of β-lactam resistance in NTHi isolates in South Korea.

This was a retrospective surveillance study based on laboratory investigations. The study was described according to the Microbiology Investigation Criteria for Reporting Objectively: a framework for the reporting and interpretation of clinical microbiology data available at https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-019-1301-1.

In total, 115 non-duplicated H. influenzae isolates from respiratory (n = 104) and blood specimens (n = 11) from 10 sentinel hospitals in the Korean Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System from January to December 2023 (Gangnam Severance Hospital, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chonnam National University Hospital, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, Jeju National University Hospital, Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital, Wonkwang University Hospital) were included in this study [8]. Bacterial identification was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (VITEK MS system; bioMérieux) [8]. The presence of a capsule was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting bexA [9] and an aggregation assay using a polyclonal antigen (Difco™ Haemophilus influenzae Serotyping Antiserum, BD).

AST was performed using the broth microdilution method with SensititreTM KRIBVPD (TREK Diagnostic Systems Ltd.) for ampicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and cefepime. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were interpreted as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), resistant (R), or non-susceptible (NS) based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M100-ED35 breakpoint [10]. H. influenzae ATCC49247 and H. influenzae ATCC49766 were used as quality-control isolates for AST.

The production of β-lactamase was determined using nitrocefin disks (Sigma-Aldrich) by observing a color change on the disk from faint yellow to light brown.

The presence of blaTEM and blaROB was confirmed by PCR in all isolates [11]. The primers used for PCR are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli ATCC35218 was used as the positive control for blaTEM. No positive control isolates for blaROB were available. Therefore, we synthesized ROB-1 (National Center for Biotechnology Information Reference Sequence NG_049977; 918 bp) and transformed the pBHA vector by cloning the synthesized ROB-1 into E. coli DH5α. This isolate was used as the positive control for blaROB.

Table 1. Primers used in the study

| Target genes | Primer name | Sequences (5’→3′) | Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | TEM (321) | TGGGTGCACGAGTGGGTTAC | 526 | [11] |

| TEM (846) | TTATCCGCCTCCATCCAGTC | |||

| blaROB | ROB (419) | ATCAGCCACACAAGCCACCT | 692 | |

| ROB (1110) | GTTTGCGATTTGGTATGCGA | |||

| ftsI | F1 (936) | GTTAATGCGTAACCGTGCAATTACC | 704 | [12] |

| F2 (1640) | ACCACTAATGCATAACGAGGATC | |||

| J1 (1048) | GATACTACGTCCTTTAAATTAAG | 550 | ||

| J2 (1598) | GCAGTAAATGCCACATACTTA |

The nucleotide sequence of ftsI was analyzed to identify amino acid mutations in PBP3 that confer resistance to β-lactam agents in β-lactamase-non-producing H. influenzae isolates showing resistance to ampicillin or cephalosporins [12]. The segment of ftsI used was located between nucleotides 997 and 1597 (amino acids 326–532). The ftsI allele was determined using PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/haemophilus-influenzae). Twelve common amino acid changes (D350N/S, S357N, A368P/T, M377E/ I, S385T, L389F, A437S, I449M/V, G490E/N, A502S/T/V, R517H/K, N526D/H/K) were assessed by comparing them with H. influenzae Rd KW20 reference (accession no. L42023).

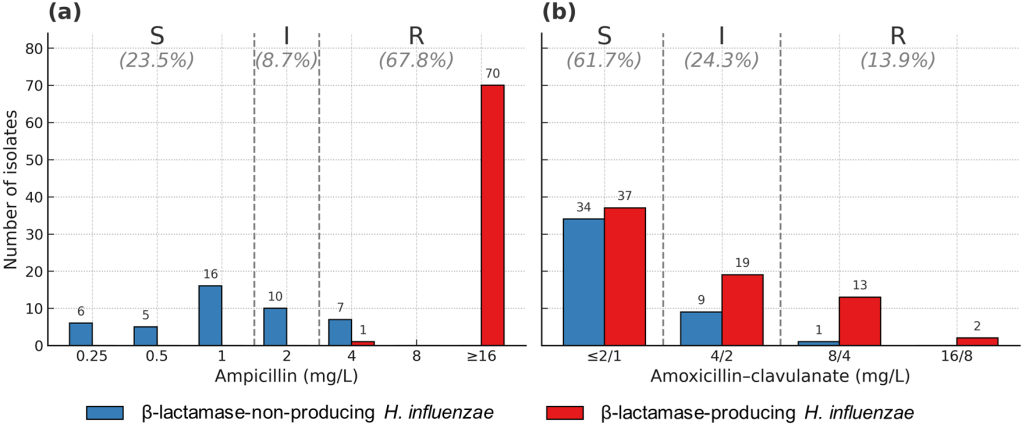

All 115 H. influenzae isolates were confirmed as NTHi by serotyping. Among the 115 NTHi isolates, 67.8% (n = 78) and 8.7% (n = 10) were resistant and intermediate to ampicillin, respectively (Fig. 1). For amoxicillin–clavulanate, 13.9% (n = 16) and 24.3% (n = 28) were resistant and intermediate, respectively. Among the 78 ampicillin-resistant isolates, 38, 24, and 16 were susceptible, intermediate, and resistant to amoxicillin–clavulanate, respectively. All 16 amoxicillin–clavulanate-resistant isolates were resistant to ampicillin. Resistance and intermediate resistance to cefuroxime were observed in 32.2% (n = 37) and 27.8% (n = 32) of the isolates, respectively. All isolates were susceptible to cefotaxime and ceftriaxone, and 4.3% (n = 5) were resistant to cefepime.

Fig. 1. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae isolates to ampicillin (a) and amoxicillin–clavulanate (b) in South Korea. S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Among 78 ampicillin-resistant isolates, β-lactamase-producing ampicillin-resistant (BLPAR) H. influenzae was observed in 71 (91.0%) isolates. Seven (9.0%) isolates were β-lactamase-non-producing ampicillin-resistant (BLNAR) H. influenzae. All BLPAR isolates carried blaTEM, and none carried blaROB. All 10 isolates with intermediate resistance to ampicillin were β-lactamase non-producers. Among 44 β-lactamase-non-producing isolates, 16 showing resistance to ampicillin and/or cephalosporins were selected for ftsI sequencing. Among the 16 amoxicillin–clavulanate-resistant isolates, 15 β-lactamase producers (BLPACR) harbored blaTEM, and 1 isolate was a β-lactamase non-producer (Table 2). Among the 71 BLPAR isolates, 15 (21.1%), 19 (26.8%), and 37 (52.1%) were resistant, intermediate, and susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulanate, respectively. Among the 37 cefuroxime-resistant isolates, 23 (62.2%) were β-lactamase producers. Three (60.0%) of 5 cefepime non-susceptible isolates produced β-lactamases.

Table 2. Amoxicillin–clavulanate susceptibility of ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae isolates

| Amoxicillin–clavulanate | Number of ampicillin-resistant isolates (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactamase producer (n = 71) | β-lactamase non-producer (n = 7) | Total (n = 78) | |

| Resistant | 15 (93.8) | 1 (6.2) | 16 (100.0) |

| Intermediate | 19 (79.2) | 5 (20.8) | 24 (100.0) |

| Susceptible | 37 (97.4) | 1 (2.6) | 38 (100.0) |

Values are presented as n (%).

PBP3 mutations were analyzed in 16 β-lactamase non-producing isolates, including 2 ampicillin-resistant isolates, 9 cefuroxime-resistant isolates, and 5 isolates resistant to both ampicillin and cephalosporins (Table 3). Among isolates resistant to both ampicillin and cephalosporins, one isolate was resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate, cefuroxime, and cefepime, and another isolate was resistant to ampicillin, cefuroxime, and cefepime. The remaining three isolates were resistant to ampicillin and cefuroxime.

Among the 12 known amino acid mutation points, 4–7 mutations per isolate were detected. S385T was most common (n = 16), followed by D350N (n = 15), S357N (n = 15), M377I (n = 13), L389F (n = 13), N526K (n = 11), R517H (n = 5), and A502T (n = 2). The most common ftsI allele was identified as allele 40 (n = 6). Alleles of 26, 16, 16-like, and 370 were detected in 4, 1, 1, and 1 isolates, respectively. Three isolates harbored this novel allele type (Table 3).

Table 3. PBP3 mutation profiles of β-lactamase-non-producing β-lactam-resistant Haemophilus influenzae

| Resistance profile | Isolates (n = 16) | TEM | ftsI allele | Amino acid substitutions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D350 | S357 | M377 | S385 | L389 | I449 | A502 | R517 | N526 | ||||

| AM | 2 | – | 40 | N | N | I | T | F | K | |||

| AM, AMC, CXM, FEP | 1 | – | NEW | N | N | T | K | |||||

| AM, CXM, FEP | 1 | – | NEW | N | N | T | K | |||||

| AM, CXM | 1 | – | NEW | N | N | T | K | |||||

| AM, CXM | 2 | – | 26 | N | N | I | T | F | H | |||

| CXM | 2 | – | 26 | N | N | I | T | F | H | |||

| CXM | 4 | – | 40 | N | N | I | T | F | K | |||

| CXM | 1 | – | 16 | N | N | I | T | F | T | K | ||

| CXM | 1 | – | 16-like | N | N | I | T | F | T | K | ||

| CXM | 1 | – | 370 | I | T | F | H | |||||

Abbreviations: AM, ampicillin; AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanate; CXM, cefuroxime; FEP, cefepime.

Hib infections have declined worldwide, including in South Korea, since the introduction of the Hib vaccine [2,13]. However, the number of NTHi infections is constantly increasing across all age groups, particularly in the elderly population [14]. Therefore, it is necessary to establish strategic approaches for antibiotic treatment of NTHi infections.

Ampicillin is a primary choice for treating infections caused by H. influenzae, and the major mechanism of ampicillin resistance is the production of β-lactamase [1–4]. The Prospective Resistant Organism Tracking and Epidemiology for the Ketolide Telithromycin (PROTEKT) surveillance study (1999-2000) was performed using 2,948 H. influenzae isolates from 69 centers in 25 countries [15,16]. The PROTEKT study reported an overall resistance rate of 17.1% to ampicillin. However, the ampicillin resistance rate at 64.7% was significantly higher in South Korea. Subsequent reports from South Korea have confirmed that the resistance rate to ampicillin remains high. Kim et al. [17] reported that the resistance rate to ampicillin was 58.1% in 229 isolates between 2000 and 2005. The other two studies showed high ampicillin resistance rates of 73.8% in 2010 and 69.8% in 2014 from not-susceptible NTHi in children [6,12]. The ampicillin resistance rate of nasal carriage in healthy children between 2006 and 2007 was also high (51.9%, n = 223/430) in South Korea [18]. In our study, the ampicillin resistance and intermediate resistance rates were 67.8% and 8.7%, respectively, indicating that the resistance rate was still high.

In the expanded PROTEKT surveillance study, which collected 14,870 H. influenzae isolates from 137 centers in 38 countries, the β-lactamase production rate among all isolates was 15.0%, with marked inter-country variability (0%–69.7%) [19]. High rates of β-lactamase production were observed in Taiwan (67.9%, n = 127/187), South Korea (52.6%, n = 121/230), as well as in France (31.6%, n = 197/624), the USA (27.5%, n = 268/973), and Australia (22.9%, n = 141/617). Conversely, Italy (5.0%, n = 33/666), Germany (6.0%, n = 102/1,711), and Japan (8.0%, n = 147/1,833) demonstrated relatively low rates of β-lactamase production. No β-lactamase producers were found in seven countries. In our study, the β-lactamase production rate was similarly high at 61.7%, confirming that β-lactamase production remains elevated.

The two major genes encoding β-lactamases are blaTEM and blaROB, respectively. In our study, all BLPAR isolates (n = 71) were blaTEM producers, and there were no blaROB producers. Globally, blaTEM and blaROB accounted for 93.7% (range, 67.8%–100%) and 4.6% (range, 0%–30.0%) of β-lactamase-positive H. influenzae isolates between 1999 and 2003 [19]. Although blaTEM predominated in most countries, blaROB was highly prevalent in Mexico (30.0%), the USA (12.3%), and Canada (9.4%). In South Korea, the production of blaTEM has been consistently reported at high levels. It has been reported that the prevalence of blaTEM among BLPAR isolates was 99.2% (n = 120/121) in 1999–2003, 96.6% (n = 86/89) in 2000–2005, 91.6% (n = 272/283) in 2005–2006, 90.2% (n = 37/41) in 2010, and 90.0% (n = 18/20) in 2014 [6,12,17,19,20] in South Korea. In our study, 71 of 78 ampicillin-resistant isolates were classified as BLPAR carrying blaTEM. These findings confirm that ampicillin resistance in H. influenzae is largely attributable to β-lactamase production, with a dominant contribution from blaTEM in South Korea, as previously reported.

In our study, all 7 BLNAR isolates showed low-level resistance (MIC = 4 µg/mL). In contrast, the MICs of BLPAR isolates were as high as 16 µg/mL or higher, except for one isolate. All BLNAR isolates in our study had diverse PBP3 mutation patterns. PBP3 mutations without blaTEM lead to low levels of ampicillin resistance [1], and our data showed similar results. High-level resistance to ampicillin can develop when BLNAR isolates acquire blaTEM; therefore, it is crucial to continuously monitor BLNAR isolates.

In Japan, the prevalence of BLNAR isolates has been steadily increasing and has remained at 60% since 2016 [21,22]. In particular, the number of BLNAR isolates with high MICs (range 4–32µg/mL) of ampicillin has been increasing significantly [21]. Most of them are β-lactamase negative high-level ampicillinresistant H. influenzae (high-BLNAR) isolates with amino acid substitutions near the Ser-Ser-Asn motif (Ser357Asn, Met377Ile, Ser385Thr, and Leu389Phe) and an additional amino acid substitution (Asn526Lys or Arg517His). In our study, PBP mutations in all BLNAR isolates were similar to those of Japanese origin, although no isolates revealed MICs ≥ 8 µg/mL. This finding is similar to the features of BLNAR isolates recently reported in Korean children [6]. The elevated prevalence of BLNAR isolates in Japan has been attributed to the widespread use of oral cephalosporins, particularly cefdinir and cefditoren, for H. influenzae infection treatment [21,22]. Cephalosporins are often administered at relatively low doses that do not exert bactericidal effects but promote partial damage, thereby facilitating the emergence of mutations that support bacterial survival [1]. In South Korea, similar to Japan, the prescription of cephalosporins for pediatric patients remains relatively high, raising concerns about the potential increase in the prevalence of BLNAR isolates [22,23].

Resistance to amoxicillin–clavulanate can arise through several mechanisms, including β-lactamase overproduction, inhibitor-resistant blaTEM or blaROB variants, novel β-lactamases, or alterations in PBPs superimposed on β-lactamase [1,24]. In our study, 15 of 71 BLPAR isolates were BLPACR, corresponding to 13% of all isolates, which was markedly higher than that reported previously [20]. Given the extensive use of cephalosporins and amoxicillin–clavulanate in South Korea, the rapid expansion of BLPACR isolates cannot be ruled out. Therefore, the continuous surveillance of their emergence and dissemination is imperative to guide effective treatment strategies and ensure antimicrobial stewardship.

This study had a few limitations. First, a small number of isolates over only 1 year were included; thus, a larger number of isolates should be studied for a longer period of time in the future. Second, we investigated PBP mutations only in BLNAR isolates. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate mutation patterns, including those in BLPAR isolates, to identify the overall mutation pattern.

This study revealed a high prevalence of β-lactam antibiotic resistance among non-typeable H. influenzae isolates in South Korea. Most resistant isolates were β-lactamase producers carrying blaTEM, whereas a smaller proportion exhibited resistance through PBP3 mutations. These findings highlight the need for the continued surveillance of antimicrobial resistance patterns in H. influenzae.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Busan Paik Hospital (BPIRB NON2024-005) and was exempt from the requirement for patient consent.

Soo Hyun Kim has been an editorial board member since 2011, and Young Uh has been a statistical editor since 2024 of the Annals of Clinical Microbiology. However, these authors were not involved in the review of this article. No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

This research was funded by the 2024 Research Grant from the Korean Society of Clinical Microbiology.

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

1. Tristram S, Jacobs MR, Appelbaum PC. Antimicrobial resistance in Haemophilus influenzae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007;20:368-89.

2. Heinz E. The return of Pfeiffer’s bacillus: Rising incidence of ampicillin resistance in Haemophilus influenzae. Microb Genom 2018;4:e000214.

3. Gilsdorf JR. What the pediatrician should know about non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect 2015;71 Suppl 1:S10-4.

4. Shiro H, Sato Y, Toyonaga Y, Hanaki H, Sunakawa K. Nationwide survey of the development of drug resistance in the pediatric field in 2000-2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2012: evaluation of the changes in drug sensitivity of Haemophilus influenzae and patients’ background factors. J Infect Chemother 2015;21:247-56.

5. Sanbongi Y, Suzuki T, Osaki Y, Senju N, Ida T, Ubukata K. Molecular evolution of beta-lactam-resistant Haemophilus influenzae: 9-year surveillance of penicillin-binding protein 3 mutations in isolates from Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006;50:2487-92.

6. Park C, Kim KH, Shin NY, Byun JH, Kwon EY, Lee JW, et al. Genetic diversity of the ftsI gene in beta-lactamase-nonproducing ampicillin-resistant and beta-lactamase-producing amoxicillin-/clavulanic acid-resistant nasopharyngeal Haemophilus influenzae isolates isolated from children in South Korea. Microb Drug Resist 2013;19:224-30.

7. News brief: WHO releases 2024 bacterial priority pathogens list. Am J Nurs 2024;124:11.

8. Choi YC, Kim EY, Choi HJ, Kim SH, You E, Lee JY, et al. Evaluation of VITEK 2 system and VITEK MS system for the identification of Haemophilus species: a diagnostic accuracy study. Ann Clin Microbiol 2025;28:13.

9. van Ketel RJ, de Wever B, van Alphen L. Detection of Haemophilus influenzae in cerebrospinal fluids by polymerase chain reaction DNA amplification. J Med Microbiol 1990;33:271-6.

10. CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 35th ed. CLSI M100ED35. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2025.

11. Tenover FC, Huang MB, Rasheed JK, Persing DH. Development of PCR assays to detect ampicillin resistance genes in cerebrospinal fluid samples containing Haemophilus influenzae. J Clin Microbiol 1994;32:2729-37.

12. Han MS, Jung HJ, Lee HJ, Choi EH. Increasing prevalence of group III penicillin-binding protein 3 mutations conferring high-level resistance to beta-lactams among nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae isolates from children in Korea. Microb Drug Resist 2019;25:567-76.

13. Wang S, Tafalla M, Hanssens L, Dolhain J. A review of Haemophilus influenzae disease in Europe from 2000-2014: challenges, successes and the contribution of hexavalent combination vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017;16:1095-105.

14. Whittaker R, Economopoulou A, Dias JG, Bancroft E, Ramliden M, Celentano LP, et al. Epidemiology of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease, Europe, 2007-2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23:396-404.

15. Hoban D and Felmingham D. The PROTEKT surveillance study: antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis from community-acquired respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2002;50 Suppl S1:49-59.

16. Inoue M, Lee NY, Hong SW, Lee K, Felmingham D. PROTEKT 1999-2000: a multicentre study of the antibiotic susceptibility of respiratory tract pathogens in Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2004;23:44-51.

17. Kim IS, Ki CS, Kim S, Oh WS, Peck KR, Song JH, et al. Diversity of ampicillin resistance genes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in Haemophilus influenzae isolates isolated in Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:453-60.

18. Bae SM, Lee JH, Lee SK, Yu JY, Lee SH, Kang YH. High prevalence of nasal carriage of beta-lactamase-negative ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in healthy children in Korea. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:481-9.

19. Farrell DJ, Morrissey I, Bakker S, Buckridge S, Felmingham D. Global distribution of TEM-1 and ROB-1 beta-lactamases in Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;56:773-6.

20. Bae S, Lee J, Lee J, Kim E, Lee S, Yu J, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Haemophilus influenzae respiratory tract isolates in Korea: results of a nationwide acute respiratory infections surveillance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:65-71.

21. Honda H, Sato T, Shinagawa M, Fukushima Y, Nakajima C, Suzuki Y, et al. Multiclonal expansion and high prevalence of β-lactamase-negative Haemophilus influenzae with high-level ampicillin resistance in Japan and susceptibility to quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62:e00851-18.

22. Hasegawa K, Yamamoto K, Chiba N, Kobayashi R, Nagai K, Jacobs MR, et al. Diversity of ampicillin-resistance genes in Haemophilus influenzae in Japan and the United States. Microb Drug Resist 2003;9:39-46.

23. Kim YA, Park YS, Youk T, Lee H, Lee K. Changes in antimicrobial usage patterns in Korea: 12-year analysis based on database of the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort. Sci Rep 2018;8:12210.

24. Doern GV, Brueggemann AB, Pierce G, Holley Jr. HP, Rauch A. Antibiotic resistance among clinical isolates of Haemophilus influenzae in the United States in 1994 and 1995 and detection of beta-lactamase-positive isolates resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanate: results of a national multicenter surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997;41:292-7.

1. Tristram S, Jacobs MR, Appelbaum PC. Antimicrobial resistance in Haemophilus influenzae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007;20:368-89.

2. Heinz E. The return of Pfeiffer’s bacillus: Rising incidence of ampicillin resistance in Haemophilus influenzae. Microb Genom 2018;4:e000214.

3. Gilsdorf JR. What the pediatrician should know about non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect 2015;71 Suppl 1:S10-4.

4. Shiro H, Sato Y, Toyonaga Y, Hanaki H, Sunakawa K. Nationwide survey of the development of drug resistance in the pediatric field in 2000-2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2012: evaluation of the changes in drug sensitivity of Haemophilus influenzae and patients’ background factors. J Infect Chemother 2015;21:247-56.

5. Sanbongi Y, Suzuki T, Osaki Y, Senju N, Ida T, Ubukata K. Molecular evolution of beta-lactam-resistant Haemophilus influenzae: 9-year surveillance of penicillin-binding protein 3 mutations in isolates from Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006;50:2487-92.

6. Park C, Kim KH, Shin NY, Byun JH, Kwon EY, Lee JW, et al. Genetic diversity of the ftsI gene in beta-lactamase-nonproducing ampicillin-resistant and beta-lactamase-producing amoxicillin-/clavulanic acid-resistant nasopharyngeal Haemophilus influenzae isolates isolated from children in South Korea. Microb Drug Resist 2013;19:224-30.

7. News brief: WHO releases 2024 bacterial priority pathogens list. Am J Nurs 2024;124:11.

8. Choi YC, Kim EY, Choi HJ, Kim SH, You E, Lee JY, et al. Evaluation of VITEK 2 system and VITEK MS system for the identification of Haemophilus species: a diagnostic accuracy study. Ann Clin Microbiol 2025;28:13.

9. van Ketel RJ, de Wever B, van Alphen L. Detection of Haemophilus influenzae in cerebrospinal fluids by polymerase chain reaction DNA amplification. J Med Microbiol 1990;33:271-6.

10. CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 35th ed. CLSI M100ED35. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2025.

11. Tenover FC, Huang MB, Rasheed JK, Persing DH. Development of PCR assays to detect ampicillin resistance genes in cerebrospinal fluid samples containing Haemophilus influenzae. J Clin Microbiol 1994;32:2729-37.

12. Han MS, Jung HJ, Lee HJ, Choi EH. Increasing prevalence of group III penicillin-binding protein 3 mutations conferring high-level resistance to beta-lactams among nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae isolates from children in Korea. Microb Drug Resist 2019;25:567-76.

13. Wang S, Tafalla M, Hanssens L, Dolhain J. A review of Haemophilus influenzae disease in Europe from 2000-2014: challenges, successes and the contribution of hexavalent combination vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017;16:1095-105.

14. Whittaker R, Economopoulou A, Dias JG, Bancroft E, Ramliden M, Celentano LP, et al. Epidemiology of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease, Europe, 2007-2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23:396-404.

15. Hoban D and Felmingham D. The PROTEKT surveillance study: antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis from community-acquired respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2002;50 Suppl S1:49-59.

16. Inoue M, Lee NY, Hong SW, Lee K, Felmingham D. PROTEKT 1999-2000: a multicentre study of the antibiotic susceptibility of respiratory tract pathogens in Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2004;23:44-51.

17. Kim IS, Ki CS, Kim S, Oh WS, Peck KR, Song JH, et al. Diversity of ampicillin resistance genes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in Haemophilus influenzae isolates isolated in Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:453-60.

18. Bae SM, Lee JH, Lee SK, Yu JY, Lee SH, Kang YH. High prevalence of nasal carriage of beta-lactamase-negative ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in healthy children in Korea. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:481-9.

19. Farrell DJ, Morrissey I, Bakker S, Buckridge S, Felmingham D. Global distribution of TEM-1 and ROB-1 beta-lactamases in Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;56:773-6.

20. Bae S, Lee J, Lee J, Kim E, Lee S, Yu J, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Haemophilus influenzae respiratory tract isolates in Korea: results of a nationwide acute respiratory infections surveillance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:65-71.

21. Honda H, Sato T, Shinagawa M, Fukushima Y, Nakajima C, Suzuki Y, et al. Multiclonal expansion and high prevalence of β-lactamase-negative Haemophilus influenzae with high-level ampicillin resistance in Japan and susceptibility to quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62:e00851-18.

22. Hasegawa K, Yamamoto K, Chiba N, Kobayashi R, Nagai K, Jacobs MR, et al. Diversity of ampicillin-resistance genes in Haemophilus influenzae in Japan and the United States. Microb Drug Resist 2003;9:39-46.

23. Kim YA, Park YS, Youk T, Lee H, Lee K. Changes in antimicrobial usage patterns in Korea: 12-year analysis based on database of the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort. Sci Rep 2018;8:12210.

24. Doern GV, Brueggemann AB, Pierce G, Holley Jr. HP, Rauch A. Antibiotic resistance among clinical isolates of Haemophilus influenzae in the United States in 1994 and 1995 and detection of beta-lactamase-positive isolates resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanate: results of a national multicenter surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997;41:292-7.