Laboratory Medicine Center, Division of Laboratory Medicine, GC Labs, Yongin, Korea

Correspondence to Sungwook Song, E-mail: song1221@gclabs.co.kr

Ann Clin Microbiol 2025;28(4):25. https://doi.org/10.5145/ACM.2025.28.4.6

Received on 26 September 2025, Revised on 9 December 2025, Accepted on 10 December 2025, Published on 20 December 2025.

Copyright © Korean Society of Clinical Microbiology.

This is an Open Access article which is freely available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Background: Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) is a major cause of acute respiratory infections in children and adults worldwide; however, no antiviral therapies or vaccines are currently available. Therefore, rapid and reliable diagnostic tools are required to support timely patient management and control outbreaks.

Methods: We retrospectively evaluated GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test results using 165 consecutive clinical samples collected from patients with suspected respiratory infections between May and August 2024. Specimens were pre-characterized using a confirmatory reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assay. Diagnostic performance was summarized using percent positive agreement (PPA), percent negative agreement (NPA), and overall percent agreement (OPA), with subgroup analyses by age and cycle threshold (Ct) groups.

Results: The GenBody assay achieved a PPA of 92.7% (51/55), NPA of 100% (110/110), and OPA of 97.6% (161/165), with no false-positive results. Age-stratified analysis showed high PPA in infants (93.3%) and children (97%), whereas estimates in hMPV-positive adolescents (n = 2) and adults (n = 5) were less precise owing to the small sample size. In the Ct-stratified analysis, PPA was 100% for specimens with Ct ≤ 28 (39/39), whereas all false-negative results occurred in the Ct > 28 group (12/16).

Conclusion: In this retrospective, single-center evaluation, the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test showed high agreement with RT-qPCR, with reduced detection in specimens with higher Ct values. Further prospective studies and long-term stability assessments are warranted to confirm the performance across a broader range of clinical settings and storage conditions.

Metapneumovirus, Rapid diagnostic tests, Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) is the causative agent of acute respiratory and lower respiratory tract diseases [1]. It was first detected in children with respiratory tract infections in 2001 [2]. In 2018, up to 14.2 million cases of hMPV were reported in children aged < 5 years worldwide, resulting in 7,700 in-hospital deaths. Moreover, it is estimated that 6% of severely hospitalized, radiographically confirmed patients with pneumonia are diagnosed with hMPV, making it the second most frequent viral pathogen after human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection [3].

hMPV shares many similarities with RSV [1,4]. As with many respiratory infections, hMPV and RSV seasons overlap [1]. Given these similarities, overlapping seasons, and their indistinguishability using current clinical and radiographic tests [1,4], utilization of the hMPV Ag Rapid Test Kit is important as it helps identify high-risk patients who require close monitoring and provide timely intervention. This is particularly important because treatments for RSV exist, such as ribavirin and monoclonal antibodies (palivizumab, nirsevimab), whereas hMPV has no direct therapy and requires different treatment strategies [2], including mechanical ventilation. In addition, rapid confirmation of hMPV can help avoid unnecessary empirical antibiotic therapy and repeated diagnostic workups in children, thereby improving patient management and overall resource utilization [5].

This is important, as recent events have seen an escalated increase in patients with hMPV, initially within China, but spanning across many countries, such as the USA, India, the UK, Malaysia, Kazakhstan, and Pakistan [6]. Although the World Health Organization has declared that the elevation in hMPV infection is within the seasonal respiratory pathogen detection range in the Northern Hemisphere [7], recent epidemiological data show a 17% increase in hMPV-related hospital admissions in 2025 compared with 2023 in the USA and China, highlighting the need for enhanced surveillance and public health preparedness [6]. Similar trends were observed in South Korea, where the proportion of hMPV among respiratory viruses increased from 10.9% in 2017 to 18% in 2022 [8].

Fortunately, recent changes in diagnostic capabilities have led to improved strategies for diagnosing hMPV, where the previous use of traditional methods, such as cell cultures and immunofluorescence assays, has been replaced with nucleic acid–based techniques [9]. Many other methodologies are currently being developed to detect hMPV at its earliest stages, including reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), recombinase-aided amplification (RAA), clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated protein 12a (CRISPR–Cas12a), and metagenomic next-generation sequencing [10]. However, owing to the complexity of testing, dependency on high-end equipment, and lack of diagnostic infrastructure in many countries, adequate and timely testing can be difficult using both molecular and traditional methods [9]. As such, rapid antigen tests are required because they provide accessibility and accelerated viral detection with minimal testing time and high usability for both healthcare professionals and individuals [11].

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the clinical agreement between the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test and a confirmatory RT-qPCR assay using residual respiratory specimens. We further assessed the agreement across cycle threshold (Ct) strata and age groups.

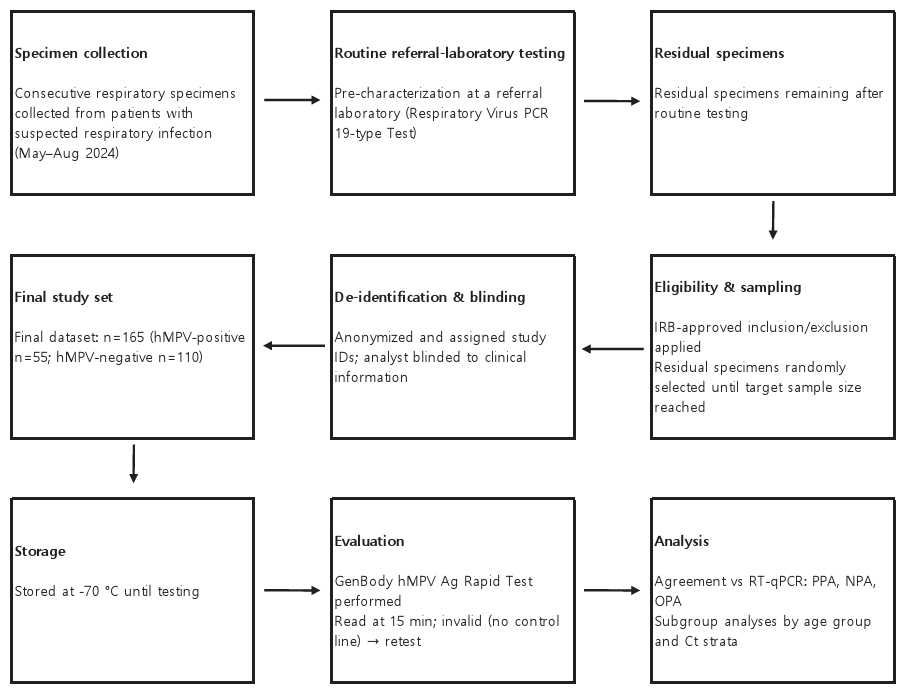

In this retrospective study, we evaluated the clinical performance and sample stability of the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test (Fig. 1). This study adheres to the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies guidelines (https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/stard/).

Respiratory specimens were consecutively collected at medical institutions from patients with suspected respiratory infection and sent to a referral laboratory for testing with the “Respiratory Virus PCR 19-type Test.” The remaining specimens were included in the study according to the IRB-approved inclusion and exclusion criteria and were randomly selected until the target sample size was reached. Multiple samples from the same patient were not included.

This was a single-center, single-blind, randomized, retrospective study. The sample collectors were responsible for specimen collection, verification of suitability, anonymization, randomization, assignment of subject identification (ID) numbers, and implementation of the blinding procedure. For anonymization, all personal identifiers were removed, and samples were randomized using a computer-generated random number list (Excel RAND function) and then sorted and assigned subject IDs sequentially. The subject ID followed the format “NNNN-000,” where NNNN corresponds to the four-digit IRB protocol number “GCL-YYYY-NNNN,” and 000 is a three-digit sequential code. The sample analyst was blinded to all information except for the subject ID.

All samples were collected between May and August 2024 and were tested using Allplex™ Respiratory Panel 2 (Ministry of Food and Drug Safety [MFDS] product license No. IVD-16-1017, Seegene Inc.) to classify hMPV-positive and hMPV-negative cases and then stored at −70°C until further testing.

Fig. 1. Outline of the testing process for performance evaluation. PCR, polymerase chain reaction; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; ID, identification; IRB, institutional review board; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; PPA, percent positive agreement; NPA, percent negative agreement; OPA, overall percent agreement; Ct, cycle threshold.

The GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test (GenBody) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Prior to testing, a nasopharyngeal swab sample was collected from the patient and stored in transport medium using one of the following: AB Transport Medium Kit (Ref. MFDS Product license no. IVD-20-1961, AB Medical Co., Ltd.), MOA UTM (Ref. MFDS Product license no. IVD-18-1571, Moa Lab Bio Inc.), MedSchenkerTM Smart Transport Medium (Ref. MFDS Product license no. IVD-20-916, Korea Standard Co., Ltd.), or Clinical Virus Transport Medium (Ref. MFDS Product license no. IVD-14-67, Noble Biosciences, Inc.). The collected samples were applied to the test device, and the results were recorded after 15 min. The appearance of a control line indicated a valid test result, whereas the appearance of a test line indicated a positive result. Any results read after 30 min or those that did not show a control line were read as invalid and were retested. For the detailed procedures, refer to the manufacturer’s instructions (accessed August 13, 2025).

DNA/RNA was extracted from the samples stored in the viral transport medium (VTM) or universal transport medium (UTM) using Magna Pure 96 (Ref. MFDS Product license no. IVD-12-2227, Roche Diagnostics Korea Co., Ltd.) and Magna Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit (Ref. MFDS Product license no. IVD-13-2880, Roche Diagnostics Korea Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer’s specifications. A total of 200 µL of samples stored in VTM or UTM were used for extraction. The extracted DNA/RNA was subjected to RT-qPCR using Allplex Respiratory Panels 2 (Ref. MFDS Product license no. IVD-16-1017, Seegene Inc.). A total volume of 25 µL was prepared by mixing 5 µL of 5× MOM, 5 µL of RNase-free Water, 5 µL of 5× Real-time One-step buffer, 2 µL of Real-time One-step enzyme, and 8 µL of the nucleic acid extract. qRT-PCR was performed using CFX96 Dx System (Ref. MFDS Product license IVD-10-205, Bio-Rad Laboratories Korea Ltd.) under the following conditions: 50°C for 20 min, 95°C for 15 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 10 s. Following the PCR, the “Seegene export” function was utilized to create a data file. The data file was uploaded to Seegene Viewer for analysis.

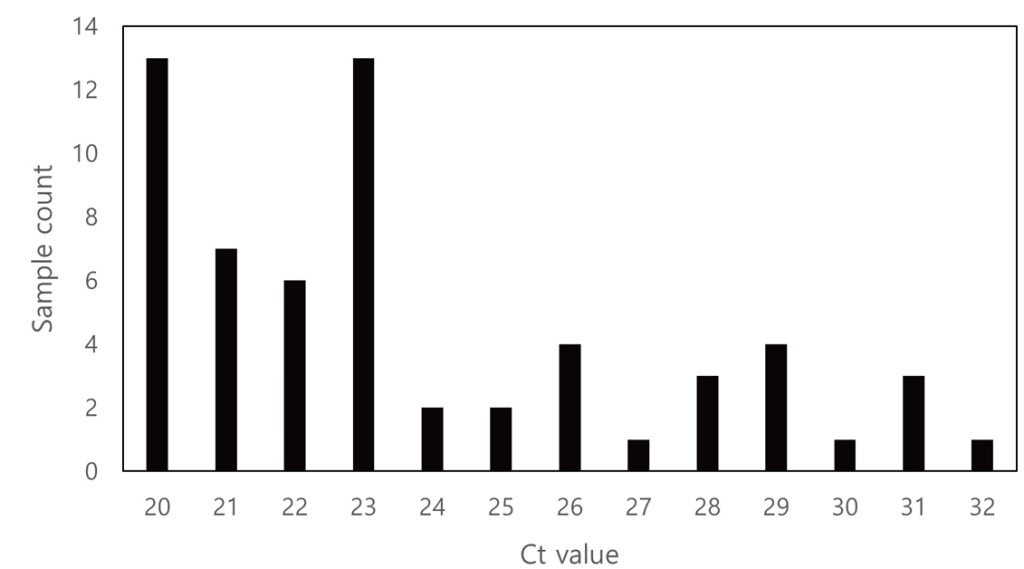

Clinical hMPV-positive specimens were stratified into three groups according to their Ct values obtained using Allplex Respiratory Panel 2 (Seegene Inc.): Ct < 24, Ct 24–28, and Ct > 28. To define these categories, a predefined positive sample was adjusted to 1× the limit-of-detection (LoD) concentration and tested in triplicate; the mean Ct value was 27.7, which was rounded to 28 and taken as the representative Ct for 1× LoD. A 10× LoD preparation of the same sample, expected to yield an approximately 3.3-cycle lower Ct than that of 1× LoD, was assigned a Ct value of 24. Accordingly, Ct values between 24 and 28 were defined as the range between the 1× and 10× LoD (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Distribution of sample count based on Ct value. Ct, cycle threshold.

The clinical and demographic variables of patients with hMPV and the diagnostic performance of the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test were evaluated using the confirmatory method.

To determine the sample size for clinical performance, peer-reviewed literature was analyzed and the calculation was performed using the formula indicated within the “Guideline for Performance Evaluation of In Vitro Diagnostic Reagents for High-Risk Infectious Agents” published by South Korea’s MFDS:

$$\frac{(Z_{\alpha/2} + Z_{\beta})^2 \times P_1(1 – P_1)}{(P_1 – P_0)^2}$$

Parameter definitions

P1: Device’s estimated sensitivity (or specificity)

P0: Target clinical sensitivity (or specificity) representing the lower bound of the confidence interval

Zα/2: Standard normal critical value for a two-sided type I error α

Zβ: Standard normal critical value for type II error β

Using data obtained from the clinical study, the following parameters were calculated: percent positive agreement (PPA; TP/(TP + FN)), percent negative agreement (NPA; TN/(TN + FP)), and overall percent agreement (OPA; (TP + TN)/N).

where TP = true positive, TN = true negative, FP = false positive, FN = false negative, and N = the sum of all samples.

Cohen’s Kappa was determined using the following equation:

$$\kappa = \frac{(P_o – P_e)}{(1 – P_e)}$$

where Po = observed agreement = (TP + TN)/N and Pe = expected agreement by chance = [(TP + FP)(TP + FN)+(FN + TN)(FP + TN)]/N2

McNemar’s test was performed using the following equation, where b = FP and c = FN:

$$\chi^2 = \frac{(b – c)^2}{(b + c)}$$

Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) was performed on a 2 × 2 contingency table as shown below:

$$(a \, b \, c \, d)$$

where a = TP, b = FP, c = FN, and d = TN

The exact probability of the observed table is calculated as follows:

$$P = \frac{(a + b)! (c + d)! (a + c)! (b + d)!}{a! b! c! d! (a + b + c + d)!}$$

The two-sided p-value was obtained by summing probabilities of all tables with the same margins having probabilities ≤ Pobs

The analytical specificity (cross-reactivity) was assessed using a panel of 30 respiratory pathogens. Each pathogen was tested in triplicate using the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test, and any visible test line within the read window was interpreted as positive (Table 1).

Table 1. List of pathogens tested for cross-reactivity

| No. | Pathogen name | No. | Pathogen name | No. | Pathogen name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adenovirus type 3 | 11 | Parainfluenza virus 4a | 21 | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| 2 | Adenovirus type 4 | 12 | Parainfluenza virus type 1 | 22 | Streptococcus pyogenes |

| 3 | Adenovirus type 7 | 13 | Parainfluenza virus type 2 | 23 | Respiratory syncytial virus-A culture fluid |

| 4 | Coronavirus culture fluid (229E) | 14 | Parainfluenza virus type 3 | 24 | Respiratory syncytial virus-B culture fluid |

| 5 | Coronavirus culture fluid (OC43) | 15 | Rhinovirus type 1B | 25 | Enterovirus 71 |

| 6 | Enterovirus 68 | 16 | Rhinovirus type 42 | 26 | Parainfluenza virus type 4B |

| 7 | Human coronavirus NL63 | 17 | Rhinovirus type 8 | 27 | Influenza B antigen (Yamagata Lineage) |

| 8 | SARS-CoV-2 culture fluid (USA-WA1/2020) | 18 | Candida albicans | 28 | Haemophilus influenzae |

| 9 | Influenza A (H1N1/2009) antigen | 19 | Legionella pneumophila | 29 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| 10 | Influenza A (H3N2) antigen | 20 | Mycoplasma pneumoniae strain FH | 30 | Staphylococcus aureus |

A total of 165 samples were collected between May 2024 and August 2024. Children and adults comprised the majority of the sample (45.5% and 31.5%, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2. Age distribution categories

| Group | Age | Sample Count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn | Birth to 27 days | 0 | 0 |

| Infant | 28 days to 23 months | 19 | 11.5 |

| Children | 24 months to 11 years | 75 | 45.5 |

| Adolescence | 12 years to 18 years | 7 | 4.2 |

| Adult | 19 years to 64 years | 52 | 31.5 |

| Elderly | ≥ 65 years | 12 | 7.3 |

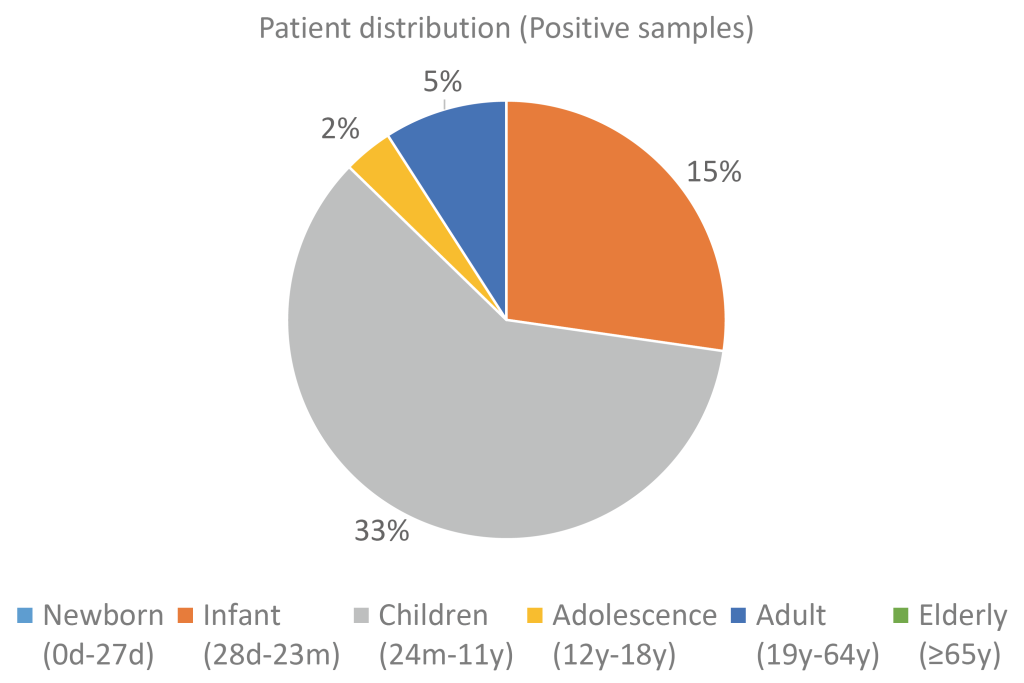

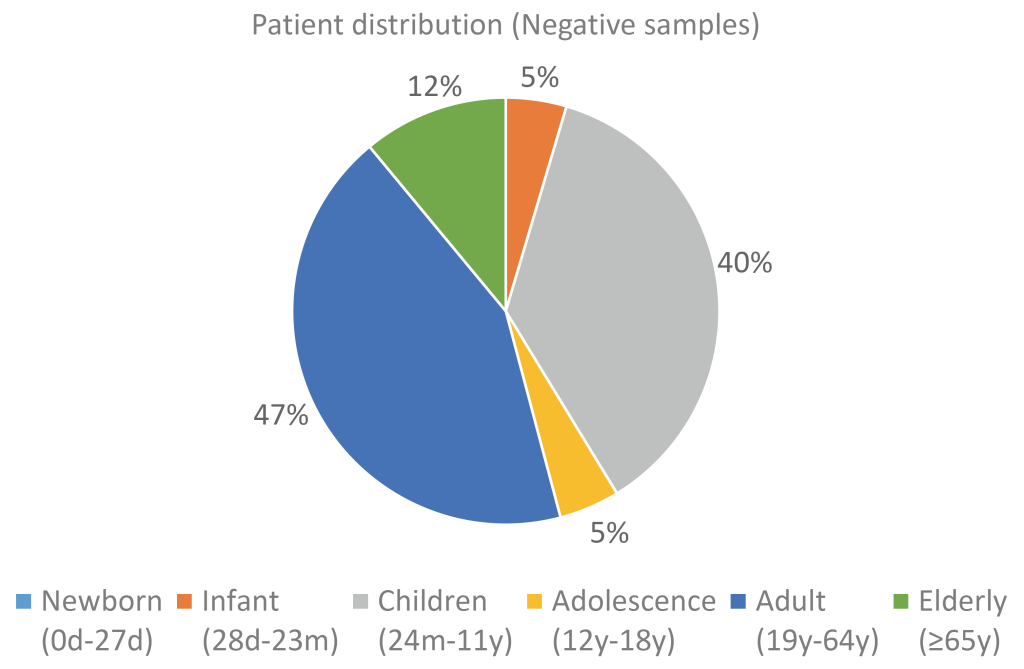

Of the 165 samples, 55 were confirmed to be positive and 110 were confirmed to be negative for hMPV. All 165 samples were confirmed to be negative for other respiratory viruses such as influenza, adenovirus, enterovirus, parainfluenza virus, bocavirus, coronavirus, and rhinovirus. For the positive samples, the age distribution was skewed toward infants (27.3%) and children (60.0%). For the negative samples, the distribution pattern was similar to that of the total sample set, with the proportions for children and adults being 36.7% and 43.1%, respectively (Fig. 3, 4).

Fig. 3. Distribution of positive samples by age group.

Fig. 4. Distribution of negative samples by age group.

The 55 positive samples and 110 negative samples were tested using the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test, and the results were compared with those obtained from the confirmatory method. To determine whether the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test agreed with the confirmatory method, the PPA and NPA were evaluated. Of the 55 positive samples, 51 were positive, whereas 4 were negative, resulting in a PPA value of 92.73%. Among the 110 negative samples, all were negative, resulting in an NPA value of 100%. The OPA in the retrospective study was 97.58%. Cohen’s K showed a value of 0.94, indicating good agreement between GenBody’s kit and the confirmatory test kit, whereas McNemar’s test showed a p-value of 0.125, showing no significant asymmetry (Table 3).

Table 3. Overall performance of the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test

| Variables | Confirmatory method | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 51 | 0 | 51 |

| Negative | 4 | 110 | 114 |

| Total | 55 | 110 | 165 |

| Overall percent agreement (OPA) | 97.58% (95% CI: 93.93%–99.05%) | ||

| Percent positive agreement (PPA) | 92.73% (95% CI: 82.74%–97.14%) | ||

| Percent negative agreement (NPA) | 100% (95% CI: 96.63%–100%) | ||

| Cohen’s K | 0.94 (95% CI: 0.88–0.99) | ||

| McNemar’s test | p = 0.125 | ||

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

The sensitivity for each age group was determined for 55 positive samples. The infant and child samples showed high sensitivity (93.3% and 97.0%, respectively). Conversely, the adolescent and adult samples showed low sensitivities of 50% and 80%, respectively. The overall sensitivity of the samples was 92.7% (Table 4).

Table 4. Positive sample distribution according to age

| Age group | Distribution (positive sample) | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Newborn (≤27 d) | 0% (0/55) | – |

| Infant (28 d–23 m) | 27.3% (15/55) | 93.3% (14/15) |

| Children (24 m–11 y) | 60.0% (33/55) | 97.0% (32/33) |

| Adolescence (12 y–18 y) | 3.6% (2/55) | 50.0% (1/2) |

| Adult (19 y–64 y) | 9.1% (5/55) | 80.0% (4/5) |

| Elderly (≥ 65 y) | 0% (0/55) | – |

| Total | 100% (55/55) | 92.7% (51/55) |

To determine whether the decrease in sensitivity was related to the age group or other factors, an additional analysis was performed. Because the Ct value from the confirmatory assay influences the rapid test performance, the sensitivity of the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test was evaluated according to the Ct categories. Among the 55 hMPV-positive samples, those with Ct values < 24 and 24–28 showed 100% sensitivity (30/30 and 9/9, respectively). By contrast, samples with a Ct > 28 showed 75% sensitivity (12/16 detected). When false-negative results were cross-referenced with age groups, reduced sensitivity was associated with higher Ct values rather than with patient age (Table 5).

Table 5. Sample distribution according to Ct values

| Ct strata | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ct values | Ct < 24 | 24 ≤ Ct ≤ 28 | 28 < Ct |

| Sample distribution | 54.54% (30/55) | 16.36% (9/55) | 29.09% (16/55) |

| Sensitivity | 100% (30/30) | 100% (9/9) | 75% (12/16) |

Abbreviation: Ct, cycle threshold

The quality of the samples was ensured by collecting them at the designated VTM or UTM, and no significant abnormalities were noted during collection. Sample integrity was further confirmed using internal control results from the confirmatory assay, where only results deemed valid by the manufacturer were considered acceptable. After confirmation, all specimens were stored at −70°C until clinical testing to maintain sample quality.

The analytical specificity of the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test was internally analyzed using 30 respiratory pathogens to determine whether there was any cross-reactivity within the test device. Three replicates were tested per pathogen, and none of the 30 pathogens showed any positivity in the device.

In this study, the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test was evaluated for its ability to detect hMPV infections. In total, 165 clinical specimens (55 positive and 110 negative) covering a wide range of age groups and Ct values were included. The assay demonstrated a PPA of 92.7% and an NPA of 100%, yielding an OPA of 97.6%. These findings highlight the excellent specificity and sensitivity of this test.

Age-stratified analysis was performed because hMPV epidemiology and clinical testing contexts differ across age groups, and prior studies have evaluated either pediatric cohorts [3,5,12,13] or older adult cohorts [14,15]. In our dataset, most positive cases were observed in infants and children, consistent with previous reports on hMPV epidemiology [1,4]. Sensitivity remained high for infants (93.3%) and children (97.0%), although small sample sizes for adolescents (n = 2) and adults (n = 5) meant that a single false result had a disproportionate impact on the calculated sensitivity (50% and 80%, respectively). False negatives (n = 4) occurred across all age groups without a consistent age-dependent pattern. When pediatric (infant + children) and non-pediatric (adolescent + adult) groups were compared, the difference was not statistically significant by Fisher’s exact test (46/48 vs. 5/7; two-sided p = 0.074), supporting interpretation of age-stratified results as descriptive rather than definitive.

Ct-stratified analysis revealed that sensitivity was strongly associated with Ct values, rather than with patient demographics. All samples with Ct < 24 and 24–28 were correctly detected (100% sensitivity), whereas false negatives occurred primarily at Ct > 28. This trend aligns with prior studies showing declining antigen test sensitivity at higher Ct values: 97.9% at Ct < 20, 54.4% at Ct > 25, and 18.7% at Ct > 30 [16]. In addition, the confirmatory assay IC supported the specimen quality, and no cross-reactivity was observed, indicating high sensitivity and specificity.

Although molecular methods such as multiplex PCR remain the gold standard [9] and alternative approaches such as immunochromatographic assays, enzyme immunoassays, and direct fluorescent antibody assays are being actively studied [12,13,14,15,17], rapid antigen detection continues to offer key advantages in accessibility and turnaround time. The GenBody assay refines these strategies with robust accuracy and user-friendly operations.

The study was not designed to investigate the causes of discordance, such as antigenic variation. Given the limited number of positive samples (n = 55) and the absence of genotyping/sequencing analysis, larger multi-site studies with balanced age representation and genotype characterization are warranted to further confirm the performance of circulating hMPV variants.

Taken together, these results suggest that rapid antigen-based testing plays a critical role in the early detection and timely management of hMPV outbreaks, particularly in settings where molecular diagnostics are less accessible. By delivering fast, accurate, and scalable results, the GenBody hMPV Ag Rapid Test can contribute significantly to epidemiological surveillance, clinical decision-making, and preparedness for seasonal or outbreak-driven increases in the hMPV burden.

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Referral Laboratory (Study no. GCL-2024-2007). Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to sample selection and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

None.

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

1. Jobe NB. Human metapneumovirus seasonality and co-circulation with respiratory syncytial virus-United States, 2014-2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2025;74:182-7.

2. Schildgen V, Van Den Hoogen B, Fouchier R, Tripp RA, Alvarez R, Manoha. Human metapneumovirus: lessons learned over the first decade. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:734-54.

3. Miyakawa R, Zhang H, Brooks WA, Prosperi C, Baggett HC, Feikin DR. Epidemiology of human metapneumovirus among children with severe or very severe pneumonia in high pneumonia burden settings: the PERCH study experience. Clin Microbiol Infect 2025;31:441-50.

4. Rima B, Collins P, Easton A, Fouchier R, Kurath G, Lamb RA. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Pneumoviridae. J Gen Virol 2017;98:2912-3.

5. Schreiner D, Groendahl B, Puppe W, Off HNT, Poplawska K, Knuf M, et al. High antibiotic prescription rates in hospitalized children with human metapneumovirus infection in comparison to RSV infection emphasize the value of point-of-care diagnostics. Infection 2019;47:201-7.

6. Adedokun KA, Adekola SA, Tajudeen A, Bello-Ibiyemi AA, Babandina MM, Magwe EA. Rising global threat of human metapneumovirus (hMPV in 2024/2025): pathogenesis, immune dynamics, vulnerabilities in immunocompromised individuals, and lessons from past pandemics. J Rare Dis 2025;4:16.

7. WHO. Disease outbreak news; trends of acute respiratory infection, including human metapneumovirus, in the Northern Hemisphere. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON550 [Online] (last visited on 10 September 2025).

8. Cho HJ, Rhee JE, Kang D, Choi EH, Lee NJ, Woo S. Epidemiology of respiratory viruses in Korean children before and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective study from national surveillance system. J Korean Med Sci 2024;39:e171.

9. Mohammadi K, Faramarzi S, Yaribash S, Valizadeh Z, Rajabi E, Ghavam M. Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) in 2025: emerging trends and insights from community and hospital-based respiratory panel analyses-a comprehensive review. Virol J 2025;22:150.

10. Feng Y, He T, Zhang B, Yuan H, Zhou Y. Epidemiology and diagnosis technologies of human metapneumovirus in China: a mini review. Virol J 2024;21:59.

11. Young SA, Zhang H, Rodriguez J, Mishkin D, Paine W, Seyfried L. Clinical evaluation of the Healgen Rapid COVID-19 antigen test as a point-of-care diagnostic tool. Immun Inflamm Dis 2025;13:e70228.

12. Matsuzaki Y, Takashita E, Okamoto M, Mizuta K, Itagaki T, Katsushima F. Evaluation of a new rapid antigen test using immunochromatography for detection of human metapneumovirus in comparison with real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47: 2981-4.

13. Kikuta H, Sakata C, Gamo R, Ishizaka A, Koga Y, Konno M. Comparison of a lateral-flow immunochromatography assay with real-time reverse transcription-PCR for detection of human metapneumovirus. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:928-32.

14. Yajima T, Takahashi H, Kimura N, Sato K, Jingu D, Ubukata S. Comparison of sputum specimens and nasopharyngeal swab specimens for diagnosis of acute human metapneumovirus-related lower respiratory tract infections in adults. J Clin Virol 2022;154:105238.

15. Hamada N, Hara K, Matsuo Y, Imamura Y, Kashiwagi T, Nakazono Y. Performance of a rapid human metapneumovirus antigen test during an outbreak in a long-term care facility. Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:424-7.

16. Garcia-Rodriguez J, Janvier F, Kill C. Key insights into respiratory virus testing: sensitivity and clinical implications. Microorganisms 2025;13:63.

17. Aslanzadeh J, Zheng X, Li H, Tetreault J, Ratkiewicz I, Meng S. Prospective evaluation of rapid antigen tests for diagnosis of respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus infections. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:1682-5.

1. Jobe NB. Human metapneumovirus seasonality and co-circulation with respiratory syncytial virus-United States, 2014-2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2025;74:182-7.

2. Schildgen V, Van Den Hoogen B, Fouchier R, Tripp RA, Alvarez R, Manoha. Human metapneumovirus: lessons learned over the first decade. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:734-54.

3. Miyakawa R, Zhang H, Brooks WA, Prosperi C, Baggett HC, Feikin DR. Epidemiology of human metapneumovirus among children with severe or very severe pneumonia in high pneumonia burden settings: the PERCH study experience. Clin Microbiol Infect 2025;31:441-50.

4. Rima B, Collins P, Easton A, Fouchier R, Kurath G, Lamb RA. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Pneumoviridae. J Gen Virol 2017;98:2912-3.

5. Schreiner D, Groendahl B, Puppe W, Off HNT, Poplawska K, Knuf M, et al. High antibiotic prescription rates in hospitalized children with human metapneumovirus infection in comparison to RSV infection emphasize the value of point-of-care diagnostics. Infection 2019;47:201-7.

6. Adedokun KA, Adekola SA, Tajudeen A, Bello-Ibiyemi AA, Babandina MM, Magwe EA. Rising global threat of human metapneumovirus (hMPV in 2024/2025): pathogenesis, immune dynamics, vulnerabilities in immunocompromised individuals, and lessons from past pandemics. J Rare Dis 2025;4:16.

7. WHO. Disease outbreak news; trends of acute respiratory infection, including human metapneumovirus, in the Northern Hemisphere. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseaseoutbreak-news/item/2025-DON550 [Online] (last visited on 10 September 2025).

8. Cho HJ, Rhee JE, Kang D, Choi EH, Lee NJ, Woo S. Epidemiology of respiratory viruses in Korean children before and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective study from national surveillance system. J Korean Med Sci 2024;39:e171.

9. Mohammadi K, Faramarzi S, Yaribash S, Valizadeh Z, Rajabi E, Ghavam M. Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) in 2025: emerging trends and insights from community and hospital-based respiratory panel analyses-a comprehensive review. Virol J 2025;22:150.

10. Feng Y, He T, Zhang B, Yuan H, Zhou Y. Epidemiology and diagnosis technologies of human metapneumovirus in China: a mini review. Virol J 2024;21:59.

11. Young SA, Zhang H, Rodriguez J, Mishkin D, Paine W, Seyfried L. Clinical evaluation of the Healgen Rapid COVID-19 antigen test as a point-of-care diagnostic tool. Immun Inflamm Dis 2025;13:e70228.

12. Matsuzaki Y, Takashita E, Okamoto M, Mizuta K, Itagaki T, Katsushima F. Evaluation of a new rapid antigen test using immunochromatography for detection of human metapneumovirus in comparison with real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47: 2981-4.

13. Kikuta H, Sakata C, Gamo R, Ishizaka A, Koga Y, Konno M. Comparison of a lateral-flow immunochromatography assay with real-time reverse transcription-PCR for detection of human metapneumovirus. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:928-32.

14. Yajima T, Takahashi H, Kimura N, Sato K, Jingu D, Ubukata S. Comparison of sputum specimens and nasopharyngeal swab specimens for diagnosis of acute human metapneumovirus-related lower respiratory tract infections in adults. J Clin Virol 2022;154:105238.

15. Hamada N, Hara K, Matsuo Y, Imamura Y, Kashiwagi T, Nakazono Y. Performance of a rapid human metapneumovirus antigen test during an outbreak in a long-term care facility. Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:424-7.

16. Garcia-Rodriguez J, Janvier F, Kill C. Key insights into respiratory virus testing: sensitivity and clinical implications. Microorganisms 2025;13:63.

17. Aslanzadeh J, Zheng X, Li H, Tetreault J, Ratkiewicz I, Meng S. Prospective evaluation of rapid antigen tests for diagnosis of respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus infections. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:1682-5.