Department of Laboratory Medicine, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

Corresponding to Jae-Woo Chung, E-mail: jwchung@dumc.or.kr

Ann Clin Microbiol 2023;26(3):51-57. https://doi.org/10.5145/ACM.2023.26.3.2

Received on 13 September 2023, Revised on 18 September 2023, Accepted on 18 September 2023, Published on 20 September 2023.

Copyright © Korean Society of Clinical Microbiology.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100 ‘Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)’ and the European Committee on AST (EUCAST) ‘Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters’ guidelines for conducting and interpreting AST are revised yearly. The 2023 CLSI guideline introduces selective and cascade reporting methods for antibacterial agents as a part of strengthening antibiotic stewardship and changes in breakpoints for aminoglycoside (AG) in Enterobacterales and AG and piperacillin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Main changes in EUCAST include revised breakpoints for aminopenicillins in Enterobacterales, and detailed criteria reflecting the clinical situation and antibacterial agent administration method.

Guidelines, Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

항균제 감수성 시험(antimicrobial susceptibility testing, AST)을 위해서는 균종에 따라 시험할 항균제의 종류를 결정하고 결과를 해석할 기준을 정해야 한다. 이에 대한 기준으로 대표적으로 사용되는 것이 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)와 the European Committee on AST (EUCAST)의 기준으로, 두 가지 모두 매년 개정이 이루어진다. 최근의 CLSI와 EUCAST 개정판의 특징을 살펴보고, 진단검사의학과에 어떻게 적용할 것인지에 대한 의견을 개진하고자 한다.

AST의 시행과 판독에 대한 CLSI의 지침인 CLSI M100, Performance Standards for AST은 매년 개정작업이 이루어지며, 2023년에는 개정 33판이 출간되었다[1]. CLSI M100은 다른 CLSI의 지침과 마찬가지로 전문가들의 자발적 참여를 통해 단계가 진행되고, 중요 과정마다 합의 과정을 거쳐서 개정된다는 특징이 있으며, 대한임상미생물학회지에서 개정 과정을 소개한 바 있다[2]. 지침의 첫부분에는 변화에 대한 개요(Overview of Changes)를 다루며, CLSI M100 개정 33판의 주요 개정 사항은 Table 1과 같다.

Table 1. Breakpoints revision in CLSI M100

| Organism | Antimicobial agent | Test/Report group | Tier | Disk diffusion (mm) | MIC (µg/mL) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | |||||||||||||||

| S | I | R | S | I | R | S | I | R | S | I | R | |||||||

| Enterobacterales | Amikacin | B | 2 | ≥ 17 | 15-16 | ≤ 14 | ≥ 20 | 17-19 | ≤ 16 | ≤ 16 | 32 | ≥ 64 | ≤ 4 | 8 | ≥ 16 | |||

| Gentamicin | A | 1 | ≥ 15 | 13-14 | ≤ 12 | ≥ 18 | 15-17 | ≤ 14 | ≤ 4 | 8 | ≥ 16 | ≤ 2 | 4 | ≥ 8 | ||||

| Tobramycin | A | 2 | ≥ 15 | 13-14 | ≤ 12 | ≥ 17 | 13-16 | ≤ 12 | ≤ 4 | 8 | ≥ 16 | ≤ 2 | 4 | ≥ 8 | ||||

| Plazomicin | – | 3 | ≥ 18 | 15-17 | ≤ 14 | ≤ 2 | 4 | ≥ 8 | ||||||||||

| Amikacin | B | U† | ≥ 17 | 15-16 | ≤ 14 | ≥ 17 | 15-16 | ≤ 14 | ≤ 16 | 32 | ≥ 64 | ≤ 16 | 32 | ≥ 64 | ||||

| Gentamycin | A | – | ≥ 15 | 13-14 | ≤ 12 | – | – | – | ≤ 4 | 8 | ≥ 16 | – | – | – | ||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Tobramycin | A | 1 | ≥ 15 | 13-14 | ≤ 12 | ≥ 19 | 13-18 | ≤ 12 | ≤ 4 | 8 | ≥ 16 | ≤ 1 | 2 | ≤ 4 | |||

| Piperacillin | O | *‡ | ≥ 21 | 15-20 | ≤ 14 | ≥ 22 | 18-21 | ≤ 17 | ≤ 16 | 32-64 | ≥ 128 | ≤ 16 | 32 | ≥ 64 | ||||

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | A | 1 | ≥ 21 | 15-20 | ≤ 14 | ≥ 22 | 18-21 | ≤ 17 | ≤ 16/4 | 32/4-64/4 | ≥ 128/4 | ≤ 16/4 | 32/4 | ≥ 64/4 | ||||

†agents reported only on organisms isolated from the urinary tract; ‡designated with an asterisk as ‘other’. Abbreviations: CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; O, other.

주요 균종의 AST 판정기준(breakpoint)의 변화를 살펴보면, Enterobacterales의 aminoglycoside (AG)와 Pseudomonas aeruginosa의 AG와 piperacillin 계열의 변경이 특징적이다. 먼저 Enterobacterales의 AG 판정기준의 변화는 2017년부터 21년까지 분리된 Enterobacterales 9,809주에 대한 AG의 활성 범위를 약동학·약력학을 기반으로 분석한 결과, amikacin의 활성 범위 적용할 때 크게 감소한 반면[3], plazomicin은 카바페넴내성장세균(carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales)에서도 최소억제농도(minimum inhibitory concentrations, MICs)가 낮게 분석된 결과들에 기반하였다[3,4]. 이는 앞선 32판에서 Enterobacterales의 piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP)의 판정기준을 변경한 것과 동일한 것으로[5], TZP의 미식품의약국(Food and Drug Administration) 권장 투여법인 3.375g 30분간 또는 4.5g 3시간 동안 6시간 간격 정맥내 주입시, 90% 이상 목표에 도달할 수 있는 MIC 값이 각각 ≤ 8 µg/mL, ≤ 16 µg/mL인 것을 기준으로, Enterobacterales의 TZP에 대한 중간(intermediate, I)와 내성(resistant, R)의 MIC 기준을 낮춘 바 있었다[5]. P. aeruginosa에서의 tobramycin 판정기준 변화는 앞선 EUCAST v12.0 판정 기준과 동일한 것으로, 2011년부터 2016년까지 SENTRY 항균제 감시프로그램 자료의 P. aeruginosa MIC가 1 µg/mL 이상인 것으로 나타난 바 있었다[6]. 마지막으로 P. aeruginosa의 TZP 판정기준 변화는 결과(outcome) 기반 임상연구에서 기존 판정기준이 임상 경과를 예측하지 못했다는 것을 반영한 것이다[7].

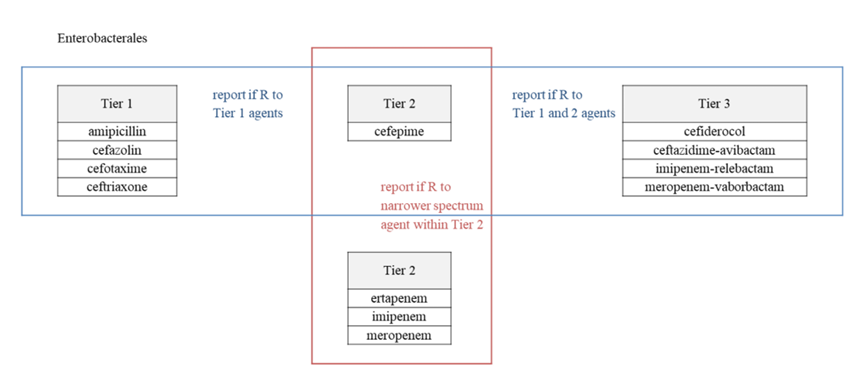

각 균주별 개별 항균제의 판정기준의 변화를 넘어선, CLSI M100 개정 33판의 가장 큰 특징은 AST 결과의 보고 체계에 선택적 보고(selective reporting)와 단계적 보고(cascade reporting)를 도입한 점이다. 두가지 모두 antimicrobial stewardship의 일환으로 잘 알려진 개념들로, 선택적 보고에 대한 예로 nitrofurantoin을 요검체 분리주에서만 전송하고, daptomycin은 호흡기 검체에서는 다루지 않으며, 1,2세대 cepha를 살모넬라증에서 전송하지 않는 등의 내용을 33판에 기술하였는데, 이는 이전 지침들의 내용과 동일하다. 반면 단계적 보고의 도입을 위해 항균제 분류의 큰 변화가 있었는데, 기존 A, B, C, D 등의 항균제 검사/보고군(Test/Report Group) [5]을 1, 2, 3, 4 등급(Tier)으로 변경하였다. 검사/보고군과 등급의 분류 개념은 기존과 유사하되, 등급의 설명에 단계적 보고가 추가되었다. 이를 부연하면, 1등급은 기존 A군과 동일한 개념으로 검사 및 보고를 모두 필수적으로 하는 등급이고, 2등급은 기존 B군으로, 기존의 1차 검사(primary testing)과 마찬가지로 기본 검사이되, 1등급에서 R일 때 단계적 보고하는 등급이나, 기관 정책에 따라 필수 검사 및 보고 대상 항균제로도 할 수 있다. 3등급은 다제내성균에 대한 기관의 정책이나 임상의의 요청에 따라 검사는 기본적으로 실시할 수 있으나, 결과는 단계적 보고에 맞춰야 하는 항균제들이며, 4등급은 기존의 D군과 동일하게 환자에게 사용할 약제가 없거나, 특이한 항균제 감수성 양상의 균주일 때, 또는 역학적 목적으로 검사하고 결과를 전송하는 등급이다. 이를 요약하면, 단계적 보고는 분리주의 전체 항균제 감수성 양상을 기반으로 특정 제제에 대한 보고 여부를 결정하는 것으로, 2 또는 3등급인 이차 항균제나 광범위제제는 1등급인 일차 항균제나 좁은 범위 항균제가 내성일때 결과를 전송하는 것이다. 예를 들어, Enterobacterales에서 1등급 항균제인 ceftriaxone (CRO)이 R이면 2등급인 cefepime (FEP) 결과를 보고할 수 있으나 반대로 CRO이 감수성(susceptible, S)이면 2등급인 FEP은 전송하지 않는 것이다(Fig. 1). 단, 이때 1등급인 좁은 범위 항균제가 S였더라도, 넓은 범위 항균제의 R은 반드시 전송해야 한다. 단, 선택적 보고나 단계적 보고를 임상적으로 적용하는 경우에는 누적 항균제 감수성(cumulative antibiogram) 통계 산출시에는 보고된 자료가 아닌 실제 검사된 자료를 사용해야 왜곡을 방지할 수 있다[8]. CLSI M100 33판에서는 균종별 새로운 항균제 분류체계를 표로서 제안하고 있으며, 1등급 항균제의 변화를 살펴보면 Enterobacterales에서는 cefotaxime, CRO, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC), ampicillin-sulbactam (SAM), TZP, ciprofloxacin (CIP), levofloxacin (LVX), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT)이 추가되었고, P. aeruginosa에서는 FEP, CIP, LVX이, Acinetobacter spp.는 FEP이, Burkholderia cepacia complex에서는 ceftazidime, LVX, minocycline (MI)이, 그외 Enterobacterales에서는 TZP, SXT가 추가되었다. 마지막으로 그람양성균에서의 변화는 Staphylococcus spp.에서 doxycycline, MI, tetracycline, vancomycin의 추가와 penicillin의 2등급 하향이 있었다.

매년 이루어지는 EUCAST의 AST 판정기준 개정은 2023년도에 Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters (version 13)이 출간되었으며, 6월 26일에 소개정판인 v 13.1이 배포되었다[9]. EUCAST v 13의 가장 큰 개정사항은 Enterobacterales에서 aminopenicillin (AP) 계열의 판정기준의 변화이다. 이는 CLSI의 개정 방향과 동일하게 AP의 약동학·약력학 정보가 증가함에 따라[10], AP 판정기준에 세밀한 조정이 필요해져서이며, 결과적으로, Enterobacterales 판정기준에 대한 표의 AP 항목은 세분화되었다(Table 2). AP의 판정기준의 변경 이유는 다음과 같다:

– ampicillin (AM), SAM, amoxicillin (AMX), AMC 등 전 세계적으로 다양한 임상 가용성 및 용도를 가진 AP의 종류들

– 경구 복용 제제와 정맥 투여형 제제 간의 전신 노출의 차이

– 경구 제제로 전신 감염의 치료 농도에 도달할 수 없음

– AM과 AMX의 감수성 예측에 AM 검사를 활용

– AP의 임상적응증이 경증에서부터 위중한 상황까지 전통적으로 매우 다양함

Table 2. New breakpoints of aminopenicillins for Enterobacterales according to infection types and formulations in EUCAST version 13

| Aminopenicillins | Formulations/Infection types | Disk diffusion (mm) | MIC (µg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | S | I | R | |||

| Ampicillin | IV | ≥14 | – | ≤13 | ≤8 | – | ≥16 | |

| Oral/uUTI only | ||||||||

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | IV | ≥14 | – | ≤13 | ≤8 | – | ≥16 | |

| Oral/uUTI only | ||||||||

| Amoxicillin | IV | ≤8 | – | ≥16 | ||||

| Oral/cUTI | – | ≤8 | ≥16 | |||||

| Oral/uUTI only | ≤8 | – | ≥16 | |||||

| Oral/other indications | ≤8 | – | ≥16 | |||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | IV | ≥19 | – | ≤18 | ≤8 | – | ≥16 | |

| Oral/cUTI | ≥19 | – | ≤18 | – | ≤8 | ≥16 | ||

| Oral/uUTI only | ≥17 | – | ≤16 | ≤32 | – | ≥64 | ||

| Oral/other indications | ≥17 | – | ≤16 | ≤8 | – | ≥16 | ||

Abbreviations: EUCAST, the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; IV, intravenous; uUTI, uncomplicated urinary tract infection; cUTI, complicated urinary tract infection.

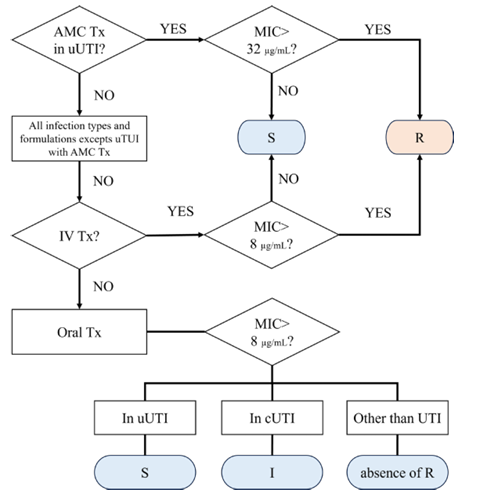

AP가 비직선적 흡수 약력학을 가진다는 문헌에서는 AP는 요배설이 높기 때문에 합병증이 없는 요로감염(uncomplicated urinary tract infection, uUTI)의 치료에 적합하며, 경구 AMC에 대한 MIC 판정기준인 S ≤ 32, R > 32 µg/mL로 하는 것은 합당하지만, 경구 AMX 단독이나 경구용 AM 또는 SAM의 기존 판정기준의 타당함을 뒷받침하는 임상 증거는 불충분하였다[10]. 그럼에도 불구하고 AM, SAM의 MIC가 ≤ 8 µg/mL인 감수성이면 안전하게 사용할 수 있다. AP는 세균성 급성신우신염의 치료에도 중요하게 사용되는데, 예를 들어AMC의 단계적 경구요법을 적용하기도 한다. 하지만, 경구용 AMC 용법을 Enterobacterales로 인한 다른 형태의 전신 감염에 적용하는 것은 부적절하고. 아울러 이 권장 사항은 AMC에 대한 내성 표현형이 예상되는 Enterobacterales에는 적용되지 않는다. 반면 정맥주사용법은 AP의 높은 혈중 농도 도달이 가능하므로, 전신 감염 등에서 사용할 수 있다. 이를 uUTI에서의 AMC 적용을 제외하고 판정기준과 함께 정리하면, AM과 AMX의 R 판정기준인 MIC > 8 µg/mL은 감염의 유형이나 약제투여 방법에 상관없이 모든 경우에 적용할 수 있다. 또한 정맥주사요법에서는 모든 감염 유형에서 MIC 8 µg/mL을 기준으로 S와 R을 구분할 수 있다. 하지만 경구요법에서는 경우의 수가 복잡한데, 우선 AM은 디스크확산법(disk diffusion, DD)과 MIC의 적용이 모두 가능하지만, AMX는 MIC 법만 가능하며, 이때 S의 기준인 AM DD ≥ 14 mm와 AM과 AMX MIC ≤ 8 µg/mL인 결과가 도출되면, uUTI에서는 AM과 AMX의 결과를 S로, 요로계 근원의 감염이면 I로, 요로계 근원이 아닌 전신감염은 내성없음(absence of R)으로 보고한다(Fig. 2). 단, 이런 흐름은 기관별 특성에 맞게 조정해서 적용해야 한다.

Fig. 2. Flowchart for implementation aminopenicillin MIC for Enterobacterales. AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; Tx, therapy; UTI, urinary tract infection; uUTI, uncomplicated UTI; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; S, susceptiblie; R, resistant; IV, intravenous; cUTI, complicated UTI; I, intermediate.

AST의 판정기준으로서 전세계적으로 널리 사용되는 CLSI와 EUCAST의 기준은 매년 개정이 이루어진다. 두 지침 모두 antibiotic stewardship의 강화와 항균제의 투약방법에 따른 약동학·약력학의 최신 연구 결과들을 반영하는 방향으로의 변화가 특징적이다. 이에 따라, 알고리즘적 보고체계인 단계적 보고 및 임상상황과 투여법에 따른 각기 다른 판정기준의 적용을 제안하고 있다. 이를 진단검사의학과에 적용하기 위해서는 임상과들과의 긴밀한 협의뿐만 아니라, 고도화된 검사정보 시스템이 필수적이다. 뿐만 아니라, 매년 개정되는 지침들의 반영을 위한 인적 물적 지원 또한 필요하다. 이를 통해 antibiotic stewardship 강화라는 선순환적 구조와 내성균 출현 최소화 및 적극적 감염관리의 기틀을 이뤄내야 한다.

항균제 감수성 시험(antimicrobial susceptibility testing, AST)의 시행과 판독에 대한 지침인 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100, Performance Standards for AST와 the European Committee on AST (EUCAST) Breakpoint tables for interpretation of minimum inhibitory concentrations and zone diameters은 매년 개정이 이루어진다. 2023년도 CLSI 지침은 antibiotic stewardship 강화의 일환으로 항균제의 선택적 보고와 단계적 보고방법이 도입되었고, Enterobacterales의 aminoglycoside (AG), Pseudomonas aeruginosa의 AG와 piperacillin 계열의 판정기준에 변화가 있었다. EUCAST의 주된 변경 사항은 Enterobacterales에서 aminopenicillin의 판정기준의 변화로, 임상상황 및 항균제 투여방법을 반영한 세분화된 판정기준이 제시되었다.

It is not a human population study; therefore, approval by the institutional review board or the obtainment of informed consent is not required.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

None.

1. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI supplement M100. 33rd ed, Wayne, PA; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2023.

2. Chang CL. Introduction of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute antibiotic susceptibility testing subcommittee meeting. Ann Clin Microbiol 2018;21:69-74.

3. Sader HS, Mendes RE, Kimbrough JH, Kantro V, Castanheira M. Impact of the recent Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoint changes on the antimicrobial spectrum of aminoglycosides and the activity of plazomicin against multidrug-resistant and carbapenemresistant Enterobacterales from United States medical centers. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023;10:ofad058.

4. Castanheira M, Sader HS, Mendes RE, Jones RN. Activity of plazomicin tested against Enterobacterales isolates collected from U.S. hospitals in 2016-2017: effect of different breakpoint criteria on susceptibility rates among aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020;64:10-1128.

5. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI supplement M100. 32nd ed, Wayne, PA; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2022.

6. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 12.0. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_12.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf [Online] (last visited on 4 September 2023).

7. Yamagishi Y, Terada M, Ohki E, Miura Y, Umemura T, Mikamo H. Investigation of the clinical breakpoints of piperacillin-tazobactam against infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Chemother 2012;18:127-9.

8. Wu H, Lutgring JD, McDonald LC, Webb A, Fields V, Blum L, et al. Selective and cascade reporting of antimicrobial susceptibility testing results and its impact on antimicrobial resistance surveillance-national healthcare safety network, April 2020 to March 2021. Microbiol Spectr 2023;11:e0164622.

9. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 13.1. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_13.1_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf [Online] (last visited on 4 September 2023).

10. de Velde F, de Winter BC, Koch BC, van Gelder T, Mouton JW. Non-linear absorption pharmacokinetics of amoxicillin: consequences for dosing regimens and clinical breakpoints. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:2909-17.

1. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI supplement M100. 33rd ed, Wayne, PA; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2023.

2. Chang CL. Introduction of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute antibiotic susceptibility testing subcommittee meeting. Ann Clin Microbiol 2018;21:69-74.

3. Sader HS, Mendes RE, Kimbrough JH, Kantro V, Castanheira M. Impact of the recent Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoint changes on the antimicrobial spectrum of aminoglycosides and the activity of plazomicin against multidrug-resistant and carbapenemresistant Enterobacterales from United States medical centers. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023;10:ofad058.

4. Castanheira M, Sader HS, Mendes RE, Jones RN. Activity of plazomicin tested against Enterobacterales isolates collected from U.S. hospitals in 2016-2017: effect of different breakpoint criteria on susceptibility rates among aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020;64:10-1128.

5. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI supplement M100. 32nd ed, Wayne, PA; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2022.

6. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 12.0. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_12.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf [Online] (last visited on 4 September 2023).

7. Yamagishi Y, Terada M, Ohki E, Miura Y, Umemura T, Mikamo H. Investigation of the clinical breakpoints of piperacillin-tazobactam against infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Chemother 2012;18:127-9.

8. Wu H, Lutgring JD, McDonald LC, Webb A, Fields V, Blum L, et al. Selective and cascade reporting of antimicrobial susceptibility testing results and its impact on antimicrobial resistance surveillance-national healthcare safety network, April 2020 to March 2021. Microbiol Spectr 2023;11:e0164622.

9. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 13.1. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_13.1_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf [Online] (last visited on 4 September 2023).

10. de Velde F, de Winter BC, Koch BC, van Gelder T, Mouton JW. Non-linear absorption pharmacokinetics of amoxicillin: consequences for dosing regimens and clinical breakpoints. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:2909-17.